This review is x-posted to Ancient Worlds

This review is x-posted to Ancient WorldsA weakened old woman falls to the floor. On her last breath, she holds her knife before her, cursing Matsu (Kaji Meiko) who is sitting by her side. Matsu delicately prises the hands open and takes the blade in her own and the old woman dies. She stands up as the already autumnal landscape turns on its brightest colors, and a sudden outburst of wind causes the leafs to fall over the body under her reverent yet determined gaze until they cover it up completely. Fall becomes winter as another gust carries away the leafs and any trace of the old woman. Time seems to come to a halt before Matsu makes a sweep of her hand holding the knive before her face, the whirlwind this time making her hair stand up, her bangs dancing like as many flames....

This is, without a shadow of doubt, the scene that you are most likely to play in your head over and over, long after you finish watching the movie. Even if the landscape is undoubtly fake (a result of the shoestring budget this genre was shot on - not that it seems to be a problem for Ito Shunya, the director), there is a quality to it that's sheer poetry, even set against the harsh words of the old woman and the piercing gaze of Matsu. And in so many ways, it encapsulates in one moment how this movie still very much ties in with the first one ("Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion") while developping, at the same time, its own identity

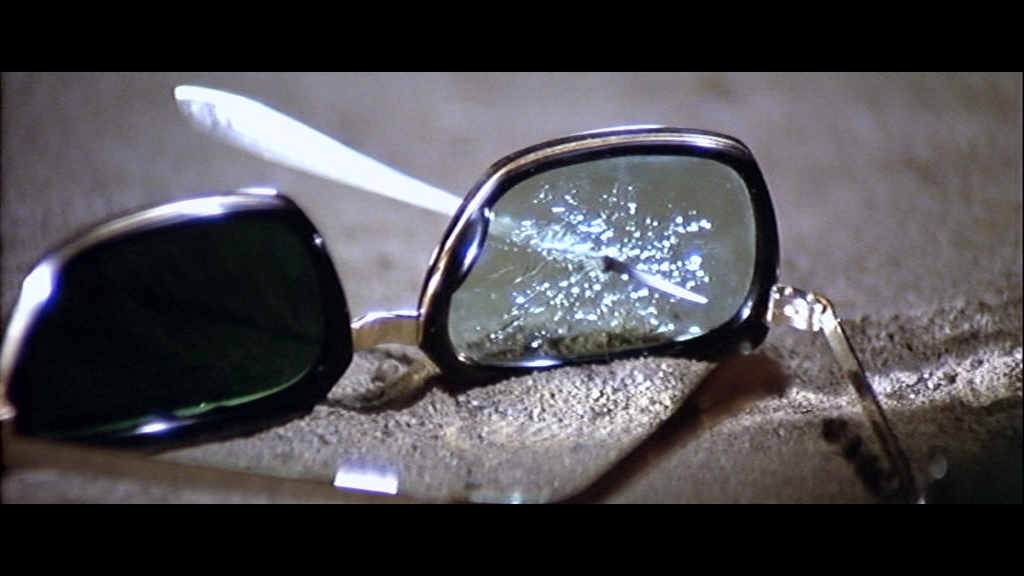

But let's backpedal a little bit. If you have seen the first movie, you won't be surprised to find a shackled Matsu - whose real name, before she fell prey to the sordid plans of her boyfriend and was sent unjustly to prison, was Nami, often nicknamed "Sasori" (Scorpion) by her fellow inmates - in a cachot down in the deepest recesses of the prison. When Goda (Watanabe Fumio), the warden, turns up, we learn that she has been placed there in isolation for a year but will be exceptionally allowed with the other prisoners as a dignitary comes for a visit. If initially the visit is uneventful, all that quickly changes when Matsu is brought in: she had hidden a blade (made out of a spoon we see her hold in her teeth and sharpen on the dirty floor meticulously throughout the whole title sequence) which she uses to attack her tormentor. The other prisoners, who had appeared docile until then, start a riot that only ends when the prison guards start to shoot

But let's backpedal a little bit. If you have seen the first movie, you won't be surprised to find a shackled Matsu - whose real name, before she fell prey to the sordid plans of her boyfriend and was sent unjustly to prison, was Nami, often nicknamed "Sasori" (Scorpion) by her fellow inmates - in a cachot down in the deepest recesses of the prison. When Goda (Watanabe Fumio), the warden, turns up, we learn that she has been placed there in isolation for a year but will be exceptionally allowed with the other prisoners as a dignitary comes for a visit. If initially the visit is uneventful, all that quickly changes when Matsu is brought in: she had hidden a blade (made out of a spoon we see her hold in her teeth and sharpen on the dirty floor meticulously throughout the whole title sequence) which she uses to attack her tormentor. The other prisoners, who had appeared docile until then, start a riot that only ends when the prison guards start to shoot Humiliated once again, Goda condemns all the inmates to hard work and arranges for Matsu to be raped by four men in front of the other women's eyes, with the hope that the public humiliation will turn them against her. He's proven right not long afterwards when, in the truck that takes them back to the prison, several inmates start beating an apparently diminished Scorpion until they believe her dead. Alarmed by one of them, the prison guards stop the truck but are attacked by a still very much alive Matsu. Seizing this opportunity, the other women team up with her, kill the men and make a run for it

Humiliated once again, Goda condemns all the inmates to hard work and arranges for Matsu to be raped by four men in front of the other women's eyes, with the hope that the public humiliation will turn them against her. He's proven right not long afterwards when, in the truck that takes them back to the prison, several inmates start beating an apparently diminished Scorpion until they believe her dead. Alarmed by one of them, the prison guards stop the truck but are attacked by a still very much alive Matsu. Seizing this opportunity, the other women team up with her, kill the men and make a run for it This event marks the start of their journey in their desperate attempt to flee the law and confinement. It also marks a clean break in terms of storyline and concept. Taken as a continuity, both Female Prisoner #701 and the first part of this movie are very much of the Women in Prison genre, but with Ito, the director, working hard at turning every single concept on its head, twisting them as far as he could without completely breaking them. But when the women escape, it's also Ito escaping from the prison of a genre: very little remains of the parade of naked bodies in the title sequence of Female Prisoner #701, and even the (fleeting) lesbian scene is relegated to the background, quite literally, of the action. Most of Jailhouse 41 is really a road movie, one that owes much to the westerns, and in particular the spaghetti westerns of Sergio Leone (how fitting, when one thinks of how much the latter owes in turn to the Japanese cinema of the 50s and 60s!), although the tone and pessimism - the sense that this can only go badly for the escapees - probably recalls more strongly Sam Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch. This filiation, Ito asserts it from the very first images of the inmates running away in a wide shot in which they run clad in long ponchos, mere points against a desolated, dry landscape

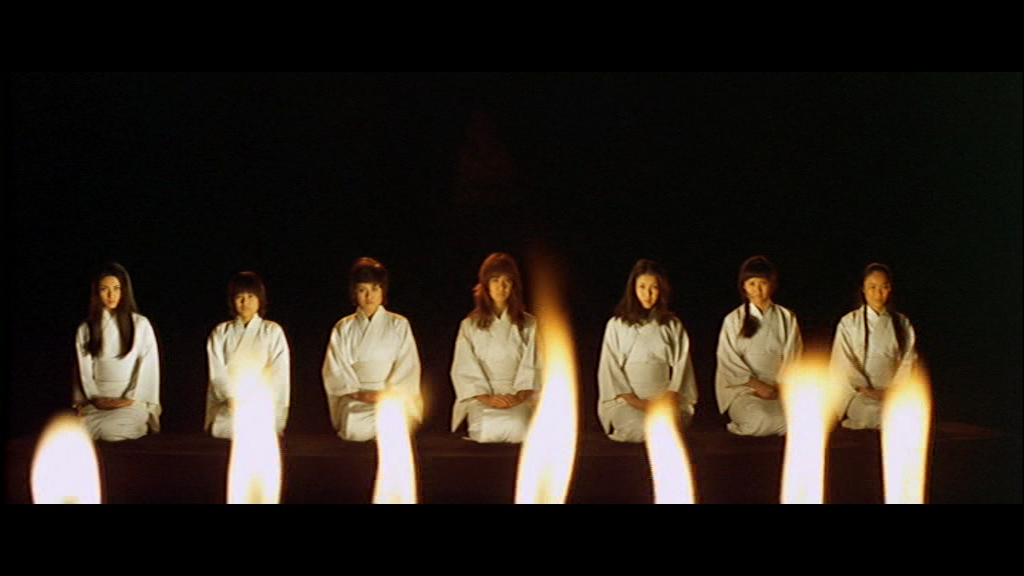

This event marks the start of their journey in their desperate attempt to flee the law and confinement. It also marks a clean break in terms of storyline and concept. Taken as a continuity, both Female Prisoner #701 and the first part of this movie are very much of the Women in Prison genre, but with Ito, the director, working hard at turning every single concept on its head, twisting them as far as he could without completely breaking them. But when the women escape, it's also Ito escaping from the prison of a genre: very little remains of the parade of naked bodies in the title sequence of Female Prisoner #701, and even the (fleeting) lesbian scene is relegated to the background, quite literally, of the action. Most of Jailhouse 41 is really a road movie, one that owes much to the westerns, and in particular the spaghetti westerns of Sergio Leone (how fitting, when one thinks of how much the latter owes in turn to the Japanese cinema of the 50s and 60s!), although the tone and pessimism - the sense that this can only go badly for the escapees - probably recalls more strongly Sam Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch. This filiation, Ito asserts it from the very first images of the inmates running away in a wide shot in which they run clad in long ponchos, mere points against a desolated, dry landscape  Another, even more striking difference with both the movie that has preceeded it, and even more so with the one that will follow, Female Prisoner Scorpion #701: Beast Stable, is the lyricism and surrealism that permeates all, even when the acts depicted are at their vilest. Already the very first scene, the one which preceeds the title sequence, sets the bar incredibly high. All we see during a single shot that lasts what seems like an eternity, is a metalic door, a door that marks the limit between the life above ground, and the world underground. As the camera goes backward, ever deeper down dark stairs, the door grows further and further away, all while a spectral voice - which is not without also recalling traditional Japanese theatre, tying neatly the kabuki-inspired sequence from the first movie to the theatrical episodes present in this one - calls for Matsu, and the angle is such that you're feeling like you're half-drowning, half-walking down to hell, which is exactly where we find Matsu when we first see her. Immediately, the tone is set with efficiency and a surprising economy of means

Another, even more striking difference with both the movie that has preceeded it, and even more so with the one that will follow, Female Prisoner Scorpion #701: Beast Stable, is the lyricism and surrealism that permeates all, even when the acts depicted are at their vilest. Already the very first scene, the one which preceeds the title sequence, sets the bar incredibly high. All we see during a single shot that lasts what seems like an eternity, is a metalic door, a door that marks the limit between the life above ground, and the world underground. As the camera goes backward, ever deeper down dark stairs, the door grows further and further away, all while a spectral voice - which is not without also recalling traditional Japanese theatre, tying neatly the kabuki-inspired sequence from the first movie to the theatrical episodes present in this one - calls for Matsu, and the angle is such that you're feeling like you're half-drowning, half-walking down to hell, which is exactly where we find Matsu when we first see her. Immediately, the tone is set with efficiency and a surprising economy of meansNo less efficient are the scenes involving the manifestation of nature: the passing of seasons at the old woman's demise, the waterfalls turning a bright bloodred to signal one of the inmates' rape and subsequent murder by passer-bys. In the former's case, as mentioned higher, it is clear that it's a studio shot, yet what could have felt cheap and cheesy due to stringent budget limitations turns to be a blessing, as once again it is completely coherent with the traditional theatre inspiration on which Ito heavily draws throughout the story

Of course, at the heart of it all is Matsu. If Meiko Kaji had made her her own in the previous installment, she is, this time around, carving her place among the pantheon of the most unforgetable characters in cinematic history - probably not too far from the "Man without a name". If she was hardly talkative in "Prisoner #701", her voice is heard here only on one occasion, so quietly that you could almost miss it if the words she said weren't so chilling. Two simple sentences, in every sense of the word: because in her mouth, those simple utterences are a condemnation of those who have betrayed her, repeatedly, just as she was trying to save them and she unflinchingly puts them to death. It is almost as if such words are the only one that she would ever use from now on, carrying the torch for the vengeful spirit they had encountered in the abandoned villages and who had passed on to her, along with the dagger, this unquenchable thirst for justice, this duty to avenge those who had wronged her, a ritual transmission that nature itself had willed

Of course, at the heart of it all is Matsu. If Meiko Kaji had made her her own in the previous installment, she is, this time around, carving her place among the pantheon of the most unforgetable characters in cinematic history - probably not too far from the "Man without a name". If she was hardly talkative in "Prisoner #701", her voice is heard here only on one occasion, so quietly that you could almost miss it if the words she said weren't so chilling. Two simple sentences, in every sense of the word: because in her mouth, those simple utterences are a condemnation of those who have betrayed her, repeatedly, just as she was trying to save them and she unflinchingly puts them to death. It is almost as if such words are the only one that she would ever use from now on, carrying the torch for the vengeful spirit they had encountered in the abandoned villages and who had passed on to her, along with the dagger, this unquenchable thirst for justice, this duty to avenge those who had wronged her, a ritual transmission that nature itself had willed But while she does not - cannot - feel regret, the demise of those women, and in particular that of Oba (brillantly played by Shiraishi Kayoko, whose grimacing face, offering a perfect contrast to Matsu's quiet intensity, reminds us of a noh mask - yet another reference to theatre), who was the leader of the gang that had escaped with her and a woman who, driven insane by a cheating husband, killed her unborn child in her own stomach and drowned her little boy, saddens her. And it is at this very moment that the early image of Matsu being tied to a tree in a way that cannot not echo Jesus on his cross, begins to make real sense. To be honest, when I first watched it, this image seemed initially a rather cheap shot, especially since Scorpion is much more avenging angel than pacifier. But seeing Matsu closing her dying comrade's eyes was very much witnessing her giving a woman who had continued to sin to the very end (Oba continues to plot her return to her island, only to burn everything to the ground), the last sacrements coming from a figure whose tears of sadness and forgiveness give her a new, almost divine dimension, a dimension further reinforced by her journey over the course of the film, having risen from the dead (her confinement underground) to attain the blinding lights of the late afternoon sun reflected by the tall buildings of Tokyo city

But while she does not - cannot - feel regret, the demise of those women, and in particular that of Oba (brillantly played by Shiraishi Kayoko, whose grimacing face, offering a perfect contrast to Matsu's quiet intensity, reminds us of a noh mask - yet another reference to theatre), who was the leader of the gang that had escaped with her and a woman who, driven insane by a cheating husband, killed her unborn child in her own stomach and drowned her little boy, saddens her. And it is at this very moment that the early image of Matsu being tied to a tree in a way that cannot not echo Jesus on his cross, begins to make real sense. To be honest, when I first watched it, this image seemed initially a rather cheap shot, especially since Scorpion is much more avenging angel than pacifier. But seeing Matsu closing her dying comrade's eyes was very much witnessing her giving a woman who had continued to sin to the very end (Oba continues to plot her return to her island, only to burn everything to the ground), the last sacrements coming from a figure whose tears of sadness and forgiveness give her a new, almost divine dimension, a dimension further reinforced by her journey over the course of the film, having risen from the dead (her confinement underground) to attain the blinding lights of the late afternoon sun reflected by the tall buildings of Tokyo city  She's given a new dimension, but at heart we recognize the Matsu we learned to love in the first installment. This same duality between break and continuity is also present at the social commentary level. It is undeniable that here, beauty, lyricism and visual experimentation - that is form, although form is never, in Ito's case, just an empty shell - are the most memorable aspects of this movie. But as you reminisce, on the heels of an explosion of colors and shapes comes the realization that it is, again, a brutal denunciation of the place of women in Japanese society, and a stark denunciation of the violence of the society itself, which is every bit as much of a cage for women as prison itself. In a way, it goes even a step further, offering an even bleaker point of view than "Prisoner #701" because then, Matsu had to fight against figures of power and authority, from warden to yakuza leaders, from corrupted policemen to prison trustees. This time however, the greatest danger comes from some of the tourists they encounter on their way, as well as from within (the inmates betraying Matsu). But we also understand that in the latters' case, it is society that has driven them to these extremes (and not the confined and specific environment of prison), which violence is illustrated in the last theatrical sequence when the fugitives are in turn condemned and beaten by villagers until Matsu stands up for them, literally, having broken free of the net that had hindered the others

She's given a new dimension, but at heart we recognize the Matsu we learned to love in the first installment. This same duality between break and continuity is also present at the social commentary level. It is undeniable that here, beauty, lyricism and visual experimentation - that is form, although form is never, in Ito's case, just an empty shell - are the most memorable aspects of this movie. But as you reminisce, on the heels of an explosion of colors and shapes comes the realization that it is, again, a brutal denunciation of the place of women in Japanese society, and a stark denunciation of the violence of the society itself, which is every bit as much of a cage for women as prison itself. In a way, it goes even a step further, offering an even bleaker point of view than "Prisoner #701" because then, Matsu had to fight against figures of power and authority, from warden to yakuza leaders, from corrupted policemen to prison trustees. This time however, the greatest danger comes from some of the tourists they encounter on their way, as well as from within (the inmates betraying Matsu). But we also understand that in the latters' case, it is society that has driven them to these extremes (and not the confined and specific environment of prison), which violence is illustrated in the last theatrical sequence when the fugitives are in turn condemned and beaten by villagers until Matsu stands up for them, literally, having broken free of the net that had hindered the others  Stunning, otherwordly, outrageous in its violence, religious references and social message, Female Convict Scorpion - Jailhouse 41 is an unclassifiable cinematic object which quality allows it to rise from the depths of a genre (often justly) not taken seriously to proudly take its place at the firmament of worldwide cinema and probably the ideal introduction to the whole Sasori series

Stunning, otherwordly, outrageous in its violence, religious references and social message, Female Convict Scorpion - Jailhouse 41 is an unclassifiable cinematic object which quality allows it to rise from the depths of a genre (often justly) not taken seriously to proudly take its place at the firmament of worldwide cinema and probably the ideal introduction to the whole Sasori series

No comments:

Post a Comment